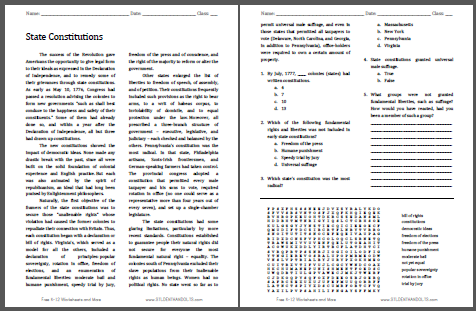

| State Constitutions Reading with Questions |

|---|

| www.studenthandouts.com ↣ American History ↣ American History Readings |

The success of the Revolution gave Americans the opportunity to give legal form to their ideals as expressed in the Declaration of Independence, and to remedy some of their grievances through state constitutions. As early as May 10, 1776, Congress had passed a resolution advising the colonies to form new governments "such as shall best conduce to the happiness and safety of their constituents." Some of them had already done so, and within a year after the Declaration of Independence, all but three had drawn up constitutions. The new constitutions showed the impact of democratic ideas. None made any drastic break with the past, since all were built on the solid foundation of colonial experience and English practice. But each was also animated by the spirit of republicanism, an ideal that had long been praised by Enlightenment philosophers.

The new constitutions showed the impact of democratic ideas. None made any drastic break with the past, since all were built on the solid foundation of colonial experience and English practice. But each was also animated by the spirit of republicanism, an ideal that had long been praised by Enlightenment philosophers.Naturally, the first objective of the framers of the state constitutions was to secure those "unalienable rights" whose violation had caused the former colonies to repudiate their connection with Britain. Thus, each constitution began with a declaration or bill of rights. Virginia's, which served as a model for all the others, included a declaration of principles: popular sovereignty, rotation in office, freedom of elections, and an enumeration of fundamental liberties: moderate bail and humane punishment, speedy trial by jury, freedom of the press and of conscience, and the right of the majority to reform or alter the government. Other states enlarged the list of liberties to freedom of speech, of assembly, and of petition. Their constitutions frequently included such provisions as the right to bear arms, to a writ of habeas corpus, to inviolability of domicile, and to equal protection under the law. Moreover, all prescribed a three-branch structure of government – executive, legislative, and judiciary – each checked and balanced by the others. Pennsylvania's constitution was the most radical. In that state, Philadelphia artisans, Scots-Irish frontiersmen, and German-speaking farmers had taken control. The provincial congress adopted a constitution that permitted every male taxpayer and his sons to vote, required rotation in office (no one could serve as a representative more than four years out of every seven), and set up a single-chamber legislature. The state constitutions had some glaring limitations, particularly by more recent standards. Constitutions established to guarantee people their natural rights did not secure for everyone the most fundamental natural right – equality. The colonies south of Pennsylvania excluded their slave populations from their inalienable rights as human beings. Women had no political rights. No state went so far as to permit universal male suffrage, and even in those states that permitted all taxpayers to vote (Delaware, North Carolina, and Georgia, in addition to Pennsylvania), office-holders were required to own a certain amount of property. |

|

+ + + + + + + S S N + + + + + + + + + + L + + D + + + + + + + + + N T O + + + + + + + + + I + + E + + + + + + + + + + O H T + + + + + + E + A + S M + + + + + + + + + + + I G Y + + + + C + + B + S O + + + + + + + + + + + + T I E + + I + + + E + E C + + + + + + + + + + + + + C R T F + + + + T + R R + S N O I T U T I T S N O C E F E + + + + A + P A + + + + + + + + + + + + + + O L O Q + + + R + E T + + + + + + + + + + + + + N + + E L U + + E + H I + + + + + + + + + + + + I + + + + F L A + D + T C + + + + + + + + + + + N + + + + + + O I L O + F I + Y T N G I E R E V O S R A L U P O P M B M + O D + + + + + + + T R I A L B Y J U R Y + + O + + M E + + + + + + + + T + + + + + + + + + + + + D + O A + + + + H U M A N E P U N I S H M E N T + + E D S + + + + + + T + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + E + + + + + + O + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + E R + + + + R + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + R + F + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + F + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + |

|

Click here to print. Answer Key: (1) C - 10, (2) D - universal suffrage, (3) C - Pennsylvania, (4) B - False, (5) Answers will vary; women, men who didn't own property, African Americans, et al. For a free interactive version of this worksheet, click here. |

|  |  |  |  |  |

| www.studenthandouts.com ↣ American History ↣ American History Readings |